This blog post will be updated regularly.

When I started my PhD, I hated writing academically. I love writing, and I have freelanced as a writer for years, but I hated writing academically. I hated the process and I hated the end-product. It is a common feeling, but I decided to study scientific writing and, more specifically, how to lend my character to it while staying within the norms. This blog post contains tricks that I learned to take control of the story, the grammar and the form of academic writing.

Accompanying this post is The Big List of Academic Writing Resources.

Before I get to the list, two points. First, function does not have to precede form. The following excerpt from a famous article by Hermann Ebbinghaus, published more than a century ago, demonstrates that form can accompany function. In the paper, he told a revolutionary story—the forgetting curve—and stayed within the constraints of grammar. The writing sounds admittedly old-fashioned and formal, but still, it waxes poetic:

The musician writes for the orchestra what his inner voice sings to him; the painter rarely relies without disadvantage solely upon the images which his inner eye presents to him; nature gives him his forms, study governs his combinations of them.

Second, stylish academic writing serves science, the reader, and you, the writer. First and foremost, it serves the science: clear writing in the service of clear science. Second, it serves your readers: your editors, your reviewers and your peers, who will approve, criticize and cite your work. Third, it serves you, the writer, in expressing your individuality and in sharing your work.

Now, without further ado, the list.

The story

Prioritize the story, the grammar and the form. The most valuable tool, in academic writing as in other forms of text, is an interesting story; no amount of style will save weak results or unsound science. The next valuable thing is that the writing fulfills its function, that of communicating; grammar is the means with which we communicate. Form, flair and flouris comes last. This is why I split the blog post into three broad (and sometimes overlapping) parts: the story, the grammar and the form. Ebbinghaus would not have afforded the form without an engrossing story and the correct grammar.

Tell your story. It sounds obvious, but it is your story to tell. Do not burden your readers with inferring the conclusions—and risk them inferring the wrong conclusions. At every step, know what your readers need and what they expect, and deliver it. Most famously, readers expect the abstract to tell them your problem, your motivation to solving it, how you solve it and to what effect.

Guide the reader. Prepare the reader for what they are about to read. Sign-post at the start of every chapter, every section and every argument. Ordinals (First …, Second…, Third…), separate your points, where one starts and another ends. Parallelism, or introducing points with the same structure, links them together. This blog post uses a lot of parallelism: each point has the tip in bold, a detailed explanation and, usually, an example at the end.

Follow a thread. A thread is a common theme in a book, its chapters and sections. Think of the thread like arcs in a TV show. A TV show has a main arc that progresses slowly over seasons—that is the TV show’s overall thread. Each season usually has its own arc, or thread, that unfolds over several episodes, all of which, in turn, have mini-arcs. Structure your arguments around the thread, and every so often, pull back towards it to remind the reader of the broader picture. For this blog post, I choose as thread story, grammar and form, and frequently refer back to the three elements.

Plan top-down. First, decide the thread for the whole book, usually your hypothesis, which gives you the chapters. Then, decide the thread for each chapter, which gives you its sections. Finally, decide the thread of each section, which gives you its paragraphs. The thread of the Methodology can be your novel algorithm’s steps.

Give each paragraph a purpose and a conclusion. A paragraph’s purpose represents its subject, and its conclusion is what you want your reader to understand. While writing, start from the subject and build an argument to finally reach your conclusion. Start and end the paragraphs with short, direct sentences: use declarative sentences. The tips in this blog post follow a similar structure: the tips in bold describe the subject and the examples give you ways to implement the tip.

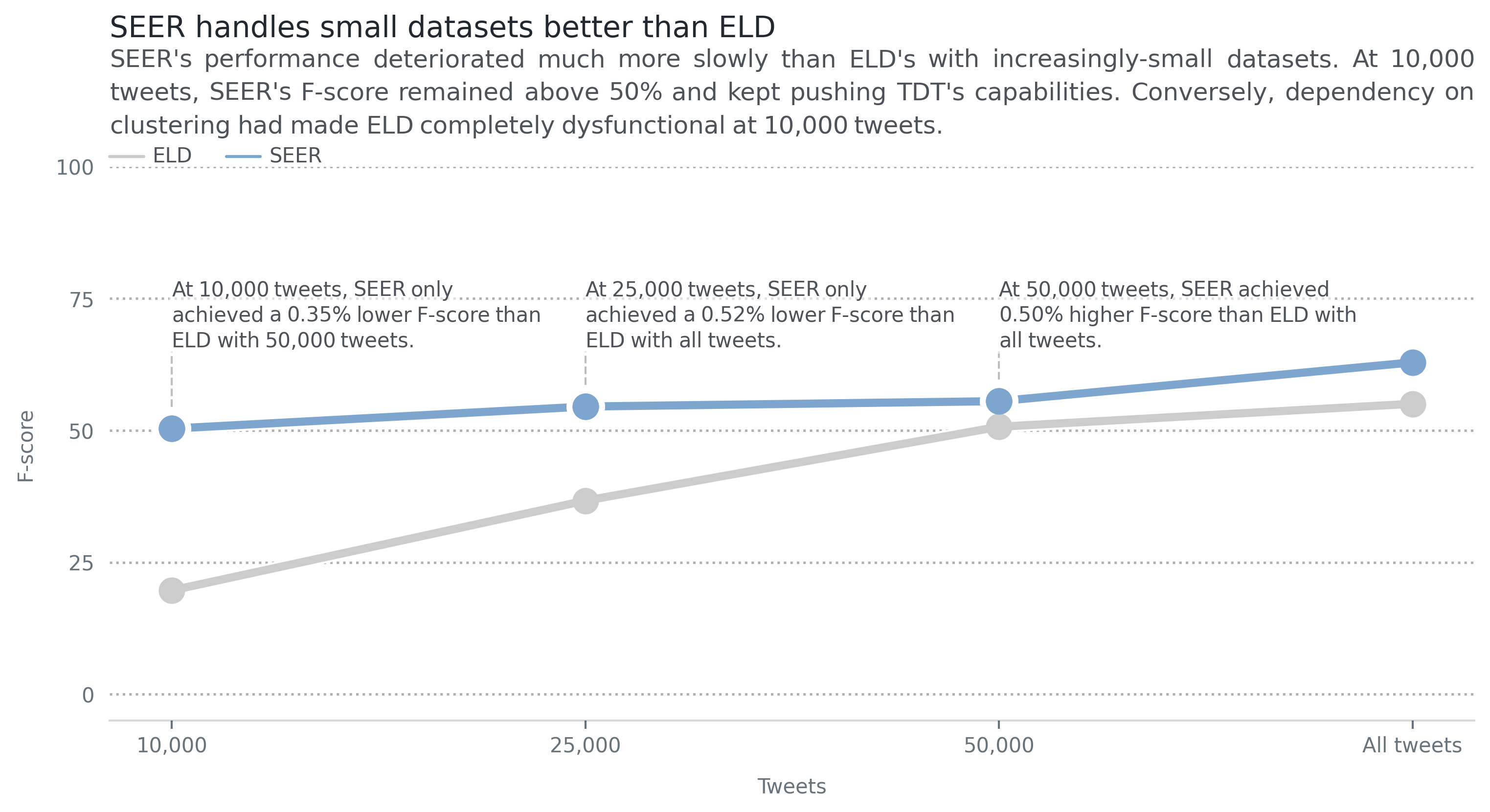

Show and tell. Visualizations are part of the story. You will only have a few visualizations in any piece of work—make them count. Remove anything that detracts from the story. In the next example, from my PhD, I highlight the main time series, and set the baseline data, against which I am comparing results, in grey.

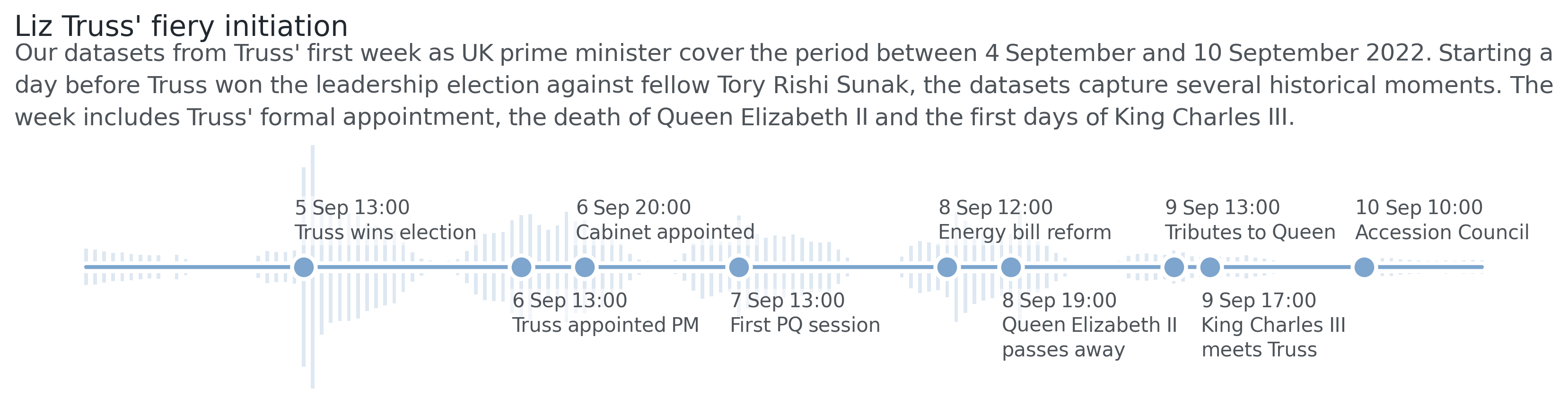

- Design readable visualizations. Visualizations should tell a story without relying on the text. Write descriptive titles with declarative sentences that describe the main conclusion. Expand the argument in a caption and, if needed, annotate interesting points with text. Where relevant, add legends and labeled axes. The next example, also from my PhD, shows how many tweets I collected for an experiment over a week.

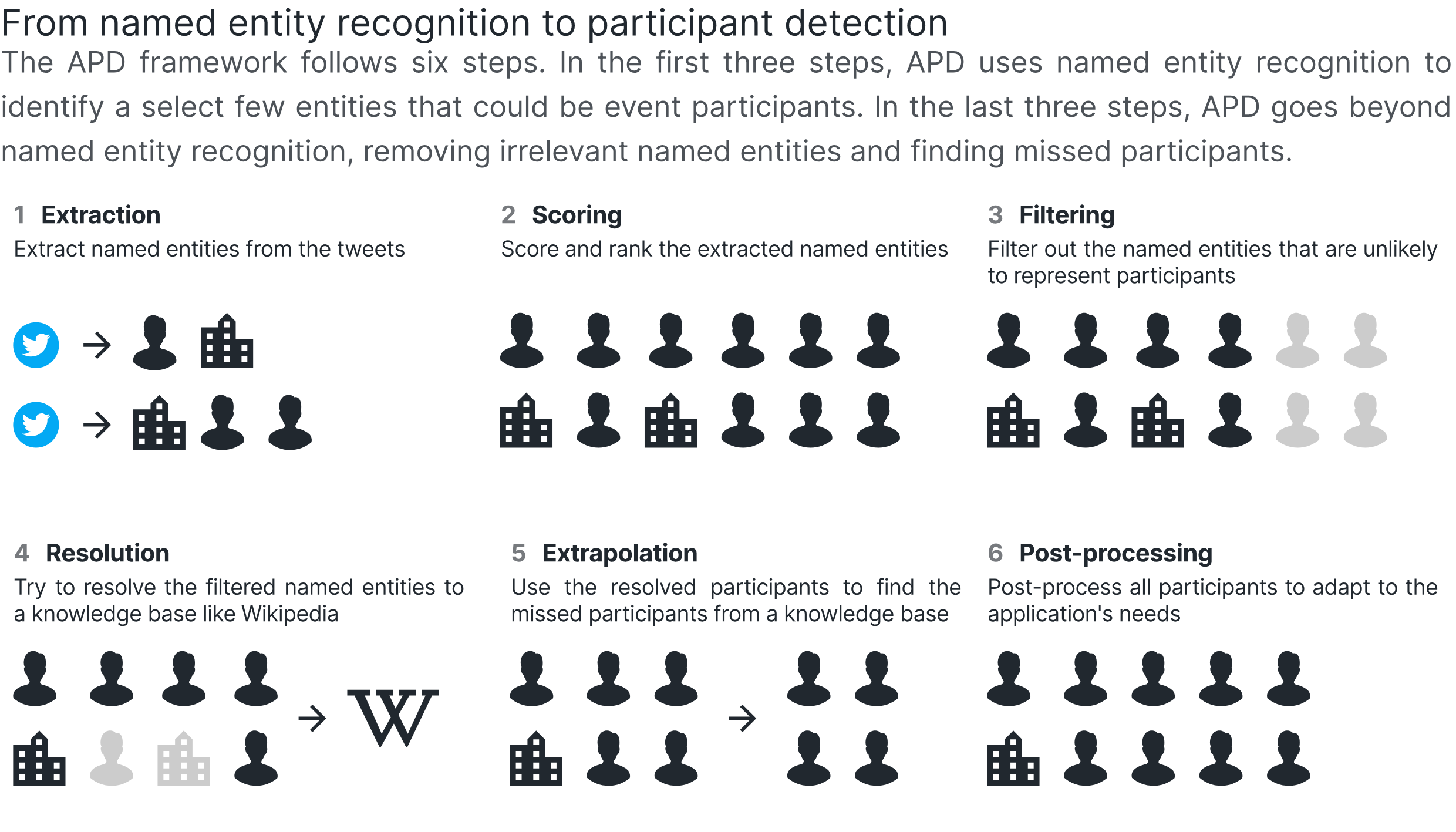

- Replace flowcharts with infographics. Flowcharts limit how much information you can write. Conversely, infographics tell a more descriptive story: they enumerate the process clearly, and can include short descriptions and examples. I took the next example from a book chapter of mine called From Event Tracking to Event Modelling: Understanding as a Paradigm Shift.

- Report significance, where possible. Statistical significance lends credence to your story. I like to report significance in two ways. First, in-line, in parentheses, with three elements: the difference between two methods, the test of significance, and the p-value: (from 36% to 54%; one-tailed paired samples t-test: p = 0.05). Second, in tables, using light and dark arrows to signify statistical significance at the 95% and 99% confidence intervals; inspired by the table on page 23 in a paper by Campos et al. (2019).

The grammar

- Know why the rules exist so you know when to break them. Distinguish between rules and rules of thumb. Grammar and style books will order you to keep your sentences short, but only because badly-written long sentences tend to be unclear. Used sparingly and edited thoroughly, long sentences can break up a monotonous rhythm, like the next long sentence from H. P. Lovecraft’s He, sandwiched by two short sentences:

He paused, but I could only nod my head. I have said that I was alarmed, yet to my soul nothing was more deadly than the material daylight world of New York, and whether this man were a harmless eccentric or a wielder of dangerous arts I had no choice save to follow him and slake my sense of wonder on whatever he might have to offer. So I listened.

Use passive verbs sparingly. As a rule of thumb, use passive verbs when you want to evoke mystery (rarely in academia), when the action is more important than the subject, or when you do not know the subject. If your statement applies broadly to the whole research area, you can use researchers or literature as the subject.

Choose the right words. There are few true synonyms, and knowing them apart comes with experience and reading, and a thesaurus. Still, choosing the right words can make the message more incisive. The word different means that two items are merely unlike each other, whereas disparate has a more powerful meaning: two things are essentially different.

Trim the text to improve the flow. You can improve the flow by removing unproductive words. You can usually remove phrases like for example and for instance; the context usually makes it obvious that you are giving examples. You can also remove phrases like we note or we argue: note what you must note; argue what you must argue. Sometimes, you might even afford to remove words like therefore or conversely.

Proofread orally. An oral proofread simply means reading the text out loud. It slows you down, does not let you skim over text that you could recite in your dreams. I call it an oral ‘proofread’ because it helps me find typos, but it also helps me find irregular rhythms.

The form

Make it short if you cannot make it interesting. My golden rule to write with style. Describing how an algorithm works will always sound more prosaic than than a literature review, or a discussion about your results. Spare your reader: keep the writing as short as possible.

Simplify the text. Simplify the sentence structure, and your arguments and choice of words. Avoid words like utilize when used performs the same function but better.

Use active verbs. You can often use more expressive verbs instead of be or have. Look for nouns that have verb forms: instead of saying that an experiment was a failure, say that the experiment failed. Similarly, use strong verbs that say what you really mean. In literature reviews, words like say hide the true meaning of your arguments; words like claim, argue or prove strengthen your writing by making it more accurate.

Give three short examples. Giving three examples lends your writing a natural rhythm and allows your readers to understand an argument better. As a rule of thumb, I give one sequence of examples every two paragraphs. A core idea in my research is understanding what happens in events: goals in football matches, overtakes in Formula 1 Grands Prix, speeches in politics.

Find one illustrative example. When writing a literature review, do not explain what researchers usually do, which leaves your readers with vague ideas. Instead, choose and describe one illustrative example, and present it as one example of what researchers usually do. Like allegories, illustrative examples help your readers visualize the argument better. In my literature reviews, I like to use illustrative examples as threads, regularly returning to them to praise or criticize different aspects.

Make an impression, go out with a bang. Readers read the introduction first, and it must hook them. They read the conclusion last, and it must linger in their minds. Helpfully, you can often get away more easily with breaking conventional rules of formal writing in the introduction and conclusion. Below, I used an anecdote to introduce an argument, that football is a simple game:

In 1990, the Italian Alps hosted the second World Cup semi-final. Germany knocked out England. After the match, Gary Lineker, whose goal for England was not enough to take his country to the final, reacted with an iconic quote: “Football is a simple game—22 men chase a ball for 90 minutes and at the end, the Germans always win.” The conclusion is not true, of course; Lineker revised his quote years later when Germany was unceremoniously knocked out of the 2018 FIFA World Cup in the group stage, but he always kept the first part: football is a simple game.

- Learn how to make an impact. Single-sentence paragraphs, colons and em-dashes, and very short sentences can all make an impact. So can breaking the ‘rules’—sparingly. To emphasize my PhD’s novelties, I used three ingredients: I wrote a short sentence, dedicated a whole paragraph to it, and started with a But:

But the research community’s solution was rarely understanding.

- Place the emphasis at the start or at the end. Readers will be reading more slowly at the start and end of sentences, so place important information there. If you intend on referring to key information in the next sentence, place key information at the end. As a counter-example, consider how the impact would have been lost if I wrote the previous example as follows:

But the research community rarely tried to understand to improve algorithms.

- Write with numbers. Numbers can anchor your argument and emphasize its impact. Saying simply that a solution reduces costs does not give the reader anything tangible; saying that a solution reduces costs tenfold does. For added impact, report figures in quick succession. I did just that to describe just how much tweet datasets change over time:

The changes to the datasets did not occur gradually. 24 hours after the match between Liverpool and Atlético de Madrid, 12.61% of tweets had already become unavailable. By then, the average number of URLs and mentions in tweets had plummeted. Twitter had removed 81.98% of tweets mentioning the word stream after one day, and the figure rose to 86.13% after one week. 14.86% of all tweets had become unavailable after just seven days.

- Conclude with shorter sentences. To signal that you are concluding, slow down the rhythm. Write shorter sentences, or shorter phrases. I ended my PhD dissertation with very short sentences:

The year is no longer 1996. The question of whether understanding can improve TDT belongs to the past. New questions can take its place. How does a TDT algorithm understand? How does it apply understanding and to what effect?

- Use callbacks. A callback means a reference to something that you wrote earlier. Callbacks go well with threads: always link back to and build upon the central argument. Compare the next example, which is how I started my PhD dissertation, and the previous example, which is how I concluded my PhD dissertation. 164 pages separate them, but the similar way I start both sentences acts as a callback:

The year is 1996. In the United States, four teams participate in the pilot study into Topic Detection and Tracking (TDT). TDT’s objective: use Artificial Intelligence (AI) to segment, detect and track news stories in the media.

Re-use technical or specific words. Re-using technical words links arguments together. Callbacks also usually depend on specific words to remind a reader of what they read before. Fiction writers give some great examples of callbacks using specific words. In The Dunwich Horror, H. P. Lovecraft refers to a protagonist as having a goatish face, training us to associate goatish features with them.

Use humor (responsibly). You can usually get away with humor, as long as you keep it classy÷ avoid puns or offensive humor, and keep it subtle. In my PhD, I used humor to introduce a section memorably:

In Paris, it is time for Le Classique, the historic rivalry between Paris Saint-Germain and Olympique de Marseille. Matches between the two French clubs are always a passionate affair, and not in the romantic ways of Paris.

- Read like a writer. I lifted the phrase from the brilliant Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose. Everyone has a different style: cultivate yours by experimenting, and yes, imitating. When you read something you like, stop and ask why you liked it and how the writer achieved the effect. I found the examples from H. P. Lovecraft in this blog post by reading closely and intentionally.